You’ve Never Read Werewolf by Night by Jenkins and Manco?! Part 1

Part I: Rejuvenating Jack Russell

Werewolves are cool. This is something that we can all agree upon as a society. The European conception of the werewolf dates at least as far back as Ancient Greece and possibly even older, and these furry monsters have since pervaded every form of modern entertainment. There have been werewolf movies, werewolf television shows, werewolf novels, werewolf video games, werewolf podcasts, and (most importantly for the selfish purposes of this piece) werewolf comic books.

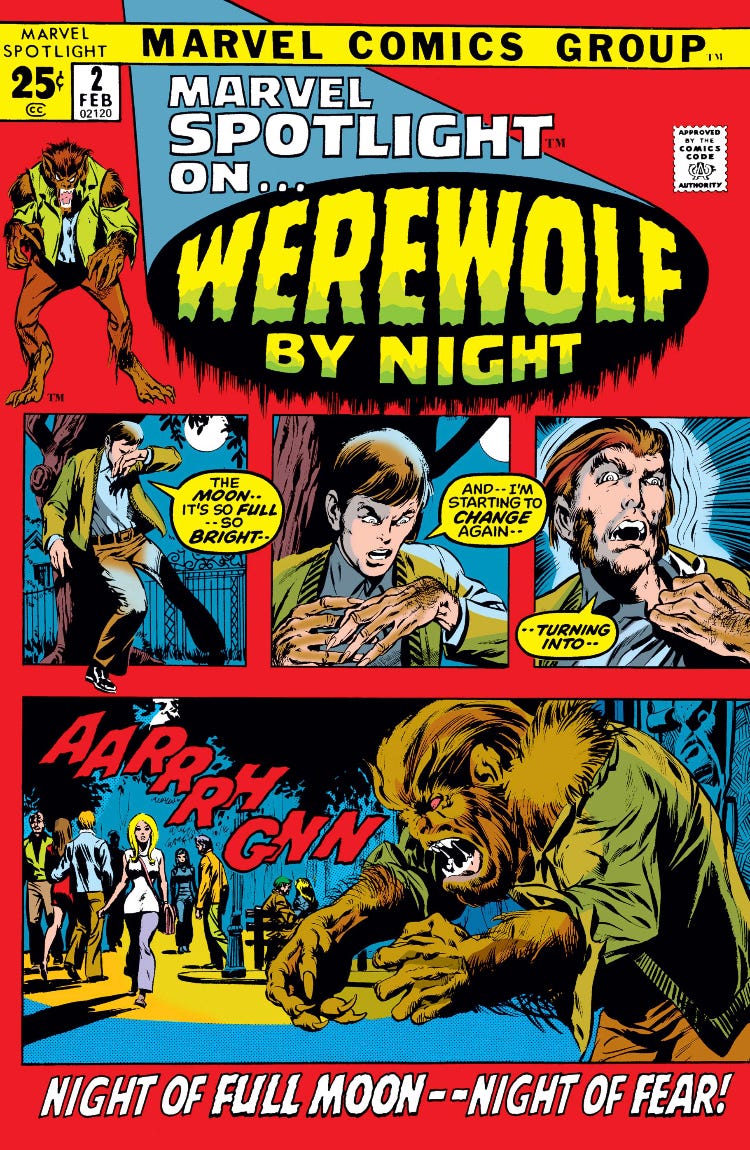

Marvel Comics got into the werewolf game in 1972 with the publication of Marvel Spotlight #2 by Gerry Conway and Mike Ploog that introduced the character of Jack Russell, the Werewolf by Night. The new character was a hit, and it led to Russell getting his own series (appropriately titled Werewolf by Night) that ran for an incredible forty-three issues from 1972 to 1977. Unfortunately, the end of the 1970s also spelled the end of Werewolf by Night as a headlining character (also, the character’s name is technically just Werewolf, but I refuse to call him anything other than Werewolf by Night). He would continue to pop up as a guest character in other series throughout the 1980s and 1990s, but it wouldn’t be until 1998 that he would once again headline his own ongoing series (oddly enough, 1998 was actually a pretty big year for the character). The creators tasked with rejuvenating the character were Paul Jenkins and Leonardo Manco.

This new Werewolf by Night series was released simultaneously with the previously discussed Man-Thing series by J.M. DeMatteis and Liam Sharp under a new Strange Tales imprint (and just like that Man-Thing series, it has never been collected in trade or made available digitally). It’s difficult to find much information on what the plans were for this imprint, but it appears that it was meant to be the label under which Marvel would publish more mature horror content. A one-shot a horror anthology comic called Strange Tales: Dark Corners #1 was also published in 1998. Regardless of what the intent might have been, Marvel certainly put some of their most talented writers and artists on these titles. Jenkins and Manco were both relative newcomers to Marvel. Manco had been the artist on multiple issues of the Hellstorm: Prince of Lies series with Len Kaminski while Jenkins was making his Marvel debut (his acclaimed Inhumans run with Jae Lee under the Marvel Knights imprint would not debut until later that year).

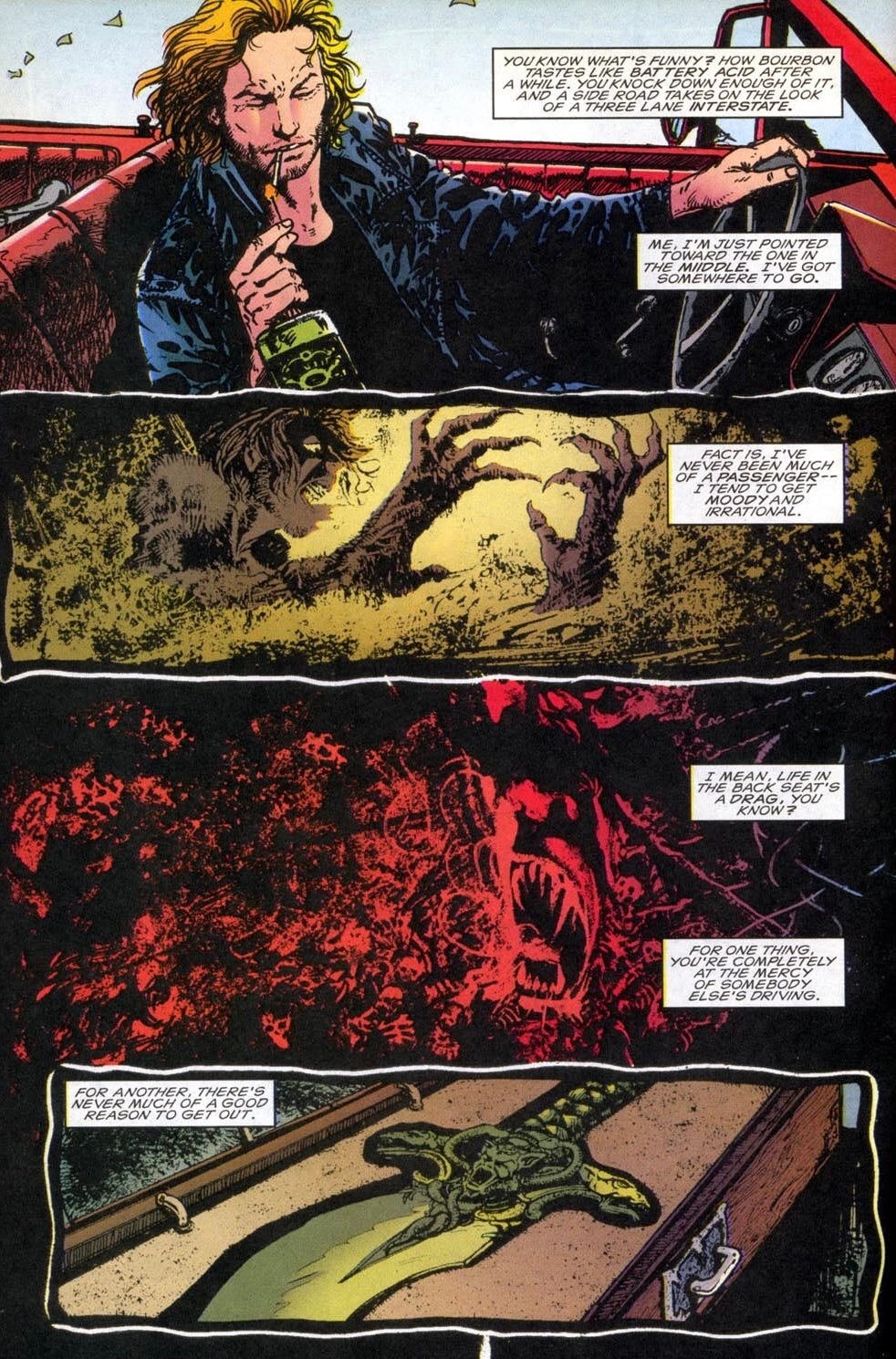

One of the first things that is established in the opening pages of Werewolf by Night #1 is that this is an older and more grizzled Jack Russell than the one from the 1970s. This Jack is more of a neo-noir antihero than the swinging young bachelor of the Bronze Age. Jack acknowledges how much his life has changed via internal monologue over the course of the first issue. We learn that Jack is living with his girlfriend (a new character named Roxana) in a modest apartment in New York City as he’s haunted by visions of himself slaughtering her in his wolf form. He spends his sleepless nights on the internet searching for possible cures for his lycanthropy. His search leads to a shadowy cult called the Third Moon (not to be confused with the Three Wolf Moon) that worships an entity controlling the wolf aspect of humanity, and they also have some sort of ceremonial blade that may or may not be exactly what Jack needs to cure himself. What could go wrong?

This leads directly into the second issue with Jack on the road searching for this cult and their magic blade. Where the comics have really shined in the early going has been the noirish sensibilities interspersed with flashes of horror buried in Jack’s subconscious that could be repressed memories of murders he has committed in his werewolf form or his own imagination conjuring images of what he might have done. It’s very effective at showing just how tortured Jack is.

As the issue nears its end, Jack does the thing that everyone is here to see: he undergoes a transformation into a werewolf! Unlike his younger days, this older Jack was not taken by surprise by his transformation. He orchestrated it to occur in the woods just outside of where this shadowy cult was located. He could have timed things just slightly better because he bursts into their lair mere seconds after they have completed a human sacrifice. Bad luck for that guy.

What transpires next is the wholesale slaughter of every single cultist on the premises by a bloodthirsty (but somewhat coherent) werewolf. The pure chaos of the next several pages is in stark contrast to the deliberately paced sequences involving Jack in human form that we’ve gotten for the first one-and-a-half issues that we’ve gotten thus far. I am a huge fan of Manco’s art in this series, but I especially love when he cuts loose with the werewolf horror.

He makes excellent use of shadow during these sequences, and every page feels like it is coated in grime. It’s some of the best horror artwork from a Big Two publisher at the time along with Liam Sharp’s contemporary work on Man-Thing. Manco’s artwork will continue to impress more and more as the series goes on and he’s given a chance to illustrate some truly disturbing sequences.

As the second issue begins to wrap up, Jack learns from one of the cult members that the ceremonial blade he’s looking for is known as the Wolfsblade and is currently broken into three pieces that must be collected and assembled. We then flash forward to Jack at a carnival where he is currently on a date with Roxana. When she leaves momentarily for a bathroom break, a mysterious stranger approaches Jack with a proposal to assist him with finding the pieces of the Wolfsblade. He’ll just have to enter Hell first.

Thus concludes the first two issues of Werewolf by Night from Jenkins and Manco. What struck me on this reread is how there are several elements common to the original 1970s series (girl trouble, magic artifacts, creepy cults, unfortunate trips to a carnival, etc.), but they are awash in the grim and gritty feel of the 1990s instead of the campiness of the 1970s.

That grim nature will only escalate in future issues. We’ll explore more of those issues next week.